Richard Cross: A Committed Photographer

Richard Cross: A Committed Photographer

By Guillermo Márquez and José Luis Benavides

Richard Cross was born on April 1, 1950, in Kansas City, Missouri to Russell Cross, a World War II veteran, and Françoise Cross, a French war bride. From an early age, Cross’s mother, Françoise, inculcated in him and his sisters a sense of pride in their French heritage and culture; she also taught them French. Thus, Cross learned the value of speaking more than one language from a very early age.

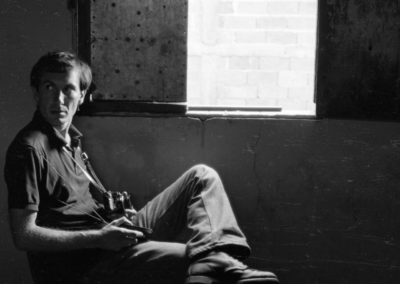

In 1968, Richard Cross attended Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, where he majored in journalism. At that university, Cross was inspired by jazz musician and sociology professor Howard Becker, a pioneer in the emergent discipline of Visual Sociology. Becker’s seminal essay, “Photography and Sociology” proposed combining methodologies and paradigms of documentary photography with those of Sociology. “It was his inspiration and encouragement in college that helped me discovered the possibilities for photography as a research method and sociological tool, as well as an art form.”[1]

Also evident in his university training is the influence of the legendary photojournalist Eugene Smith, who not only modernized the journalistic photo essay but also introduced a strong empathy for the photographed subjects, accompanied by a humanistic social conscience.[2] The emerging new photojournalism and his interest in capturing social movements from within must also have had an important influence on the young Cross. Danny Lyons’ work is one of the most notable since after being accepted as a photographer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Lyons was able to capture with his camera, from within the organization, the key moments of the civil rights movement of the 1960s in the American South.[3]

Cross also became heavily influenced by idealism and the social, political, economic, and cultural turbulence of the 1960s. Thus, he became involved with socially active organizations such as the Biafra Fund. He also nurtured a growing commitment to working with socially marginalized groups. In 1972, Pastor Cleon Poole of the Second Baptist Church in South Chicago invited Cross to photograph his congregation during a Sunday service. Some of these photos were published in the legendary African-American newspaper, The Chicago Defender, and served to revive interest and increase membership in Pastor Poole’s church.[4]

In 1972, after graduating from Northwestern University with a degree in magazine journalism, Cross called Jim Vance, the editor of Worthington, Minnesota’s Daily Globe, and asked to be interviewed for a position of staff photographer. Jim Vance and his staff were impressed by the strength of his portfolio and they quickly hired him, noting that he was well-schooled and produced high-quality work.[5]

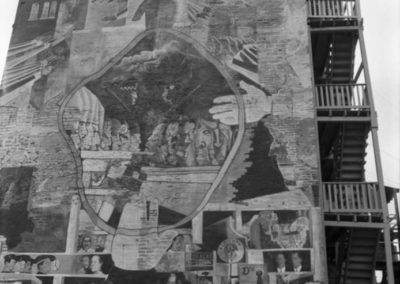

Unfortunately, Cross left the Daily Globe in late 1973, embarking on a journey to find meaning to his life’s work. Cross applied for a National Endowment for the Arts grant to continue the work he began in South Chicago, seeking to, “do a photographic essay on the spiritual and artistic expression of the black experience in Chicago’s southside black community. . . and preserve the beauty of this expression, which manifests itself not only in the religious experience but in ‘street art’ as well.”[6] The project was not funded, unfortunately, but that did not deter him. Cross continued to work as a freelancer, offering his services to different Midwestern newspapers.

————————–

[1] Cross, Richard. Grant Application to the National Endowment for the Arts, May 18, 1974.

[2] Jim Hughes’s biography of Smith is a good reference: W. Eugene Smith: Shadow & Substance: the Life and Work of an American Photographer, 1989

[3] Danny Lyons’s photographs were published in collective books and were later published in the book, Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, 2010.

[4] Cross, op. cit.

[5] Interview by Lizabeth Jamieson Menzies for her MA thesis: “Richard Cross: The Life and Death of a Photojournalist in War and Peace,” 1985, pp. 9-11.

[6] Cross, op. cit.

Colombia: The Peace Corps

Following a lengthy conversation with Jim Vance, and at his suggestion, Cross decided to enlist in the Peace Corps. On October 24, 1974, he began the Peace Corps’s training program and 14 weeks later on January 23, 1975, he took the oath, becoming a Peace Corps volunteer. Soon after, he was assigned to work in Colombia.

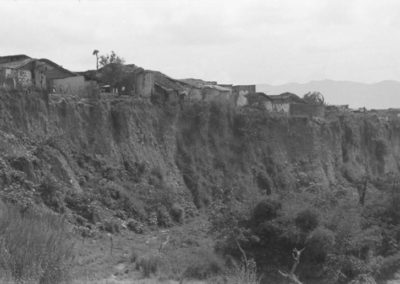

While in Colombia, he consulted with three Colombian agencies, providing his expertise and knowledge of photography. His first assignment was for the National Institute for Natural Resources (INDERENA), Colombia’s predecessor to the current Ministry of the Environment, where he photographed the effects of soil erosion in the northeastern city of Bucaramanga. As INDERENA could not afford to bring specialists to Colombia, his more than 500 black-and-white photographs, which showed the extent of erosion damage on the landscape and local attempts to control it, were sent to the Netherlands where experts could analyze the situation and make recommendations to the Colombian government.

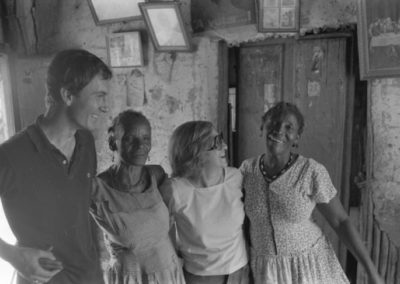

Cross also consulted for the Coffee Grower’s Federation, a semi-official agency, where his photography helped produce a presentation of cacao growing methods to help farmers across Colombia encourage its production in fertile areas to be exported as chocolate. His third project was with the Colombian Institute of Culture, where he photographed the remains of pre-Hispanic sites in San Agustín and Tierradentro. In the midst of all these official assignments, he was also able to venture into Colombian society—in search for the life and cultural diversity of the country. By the time he finished these assignments, his level of Spanish was pretty good. An inhabitant of Palenque told him at that time that it was obvious that he (Cross) was not from the coast because he could identify Cross’s accent from Bogotá. “That was the nicest feeling,” Cross said. “Not that I was a gringo or a foreigner, but that I was from Bogotá.”[1]

In June 1976, he applied for an Inter-American Press Association (IAPA) scholarship, to study the Colombian government and society well enough so he could present his observations to an American audience. More importantly, however, Cross wanted to enroll in history, economics, sociology, and political science courses, which he believed would provide him with a general overview, and thus, a better understanding of Colombian life and culture.

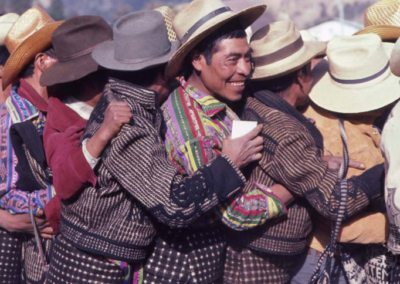

Cross studied at the University of the Andes and at Pontifical Xavierian University, both well-regarded universities in Colombia. While he was a student there, he covered various journalistic assignments, one on the Muisca civilization, and another on the First Congress of Black Culture of the Americas, held in Cali. During this time, Cross traveled through Colombia, photographing landscapes, festivals, street activities, and people.[2]

————————–

[1] June Needle wrote a press release for the Peace Corps about Richard Cross’s work: “Kansas Peace Corps Volunteer Lends Communications Skills to Colombia”. December 1, 1976.

[2] Menzies, op. cit., pp. 20-24.

Nina de Friedemann and San Basilio de Palenque

In 1975, Cross became involved in what became one of his most important works: the monumental study of the community of San Basilio de Palenque that started in 1973, funded by the Colombian Institute of Anthropology, and led by the Colombian anthropologist Nina S. de Friedemann.

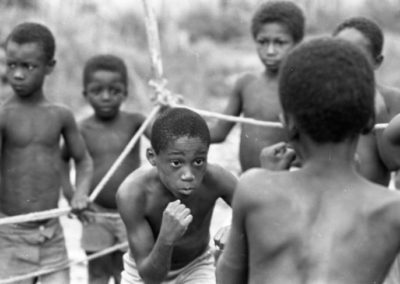

His growing interest in visual anthropology and his appreciation for Colombia encouraged Cross to work as a photographer in the investigation, which he did without any professional or financial guarantee. The project sought to study and document the historical, cultural, and social development of Afro-descendant communities along Colombia’s Atlantic coast. What began with photographing different groups of performers at the Carnaval de Barranquilla, including the group from San Basilio de Palenque known as Son de Palenque, quickly transformed into the study of the community and its inhabitants, the Palenqueros, under the leadership of Nina S. de Friedemann.

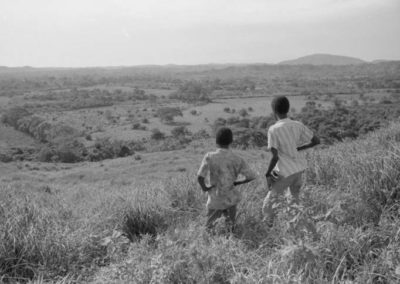

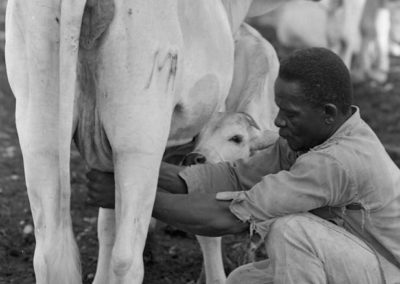

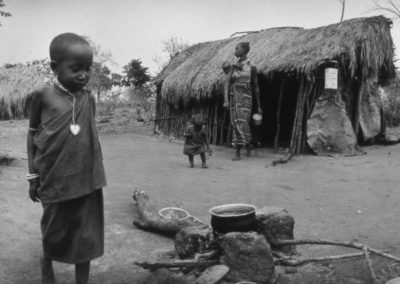

Based on Cross’s manuscript notes, the visual part of the study sought to contribute to widening departmental and national knowledge and interest in the community of San Basilio de Palenque, by (1) showing Palenque’s participation in the nation’s socio-economic spectrum as a farming and cattle-raising entity, (2) showing Palenque’s contribution to Colombian culture by reflecting some of its traditions and cultural traits whose origins are African, and (3) showing how certain factors accelerate socio-economic change in Palenque.[1]

The project, published in Ma Ngombe: Guerreros y ganaderos en Palenque, included not only the anthropological, social-historical, and visual work of its director, but also the visual anthropology work that Richard Cross would do. All of this with the participation of a committed team of allied Colombian researchers. Ma Ngombe was a pioneer in Afro-Colombian studies and also a pioneer in Latin America in successfully combining social anthropology with visual anthropology to document an Afro-American community of great linguistic, cultural and social importance for the entire continent.

In order to systematically organize his anthropological work, which began in June 1975, Cross created a visual record of San Basilio de Palenque based on five categories:

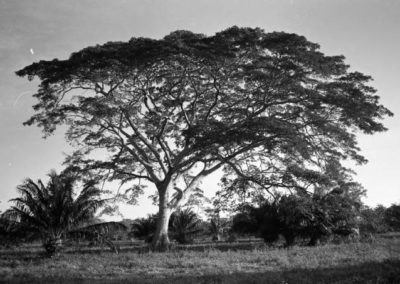

1) Aerial perspective and Palenque. Its geography, landscapes, terrain, and vegetation in order to be able to compare and contrast the physical setting, the organization, and the community with those of the ancestral communities of Africa.

2) Architecture. The exterior spaces, the walls, the ceilings, the gardens, the space between houses, the front perspective of the houses. And the interior spaces, such as the walls, the functional use of the space, the objects, the furniture.

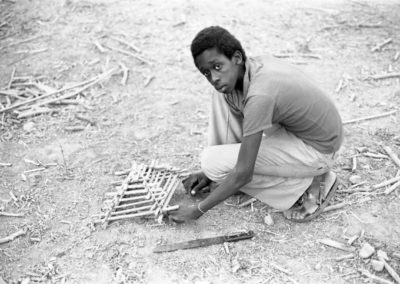

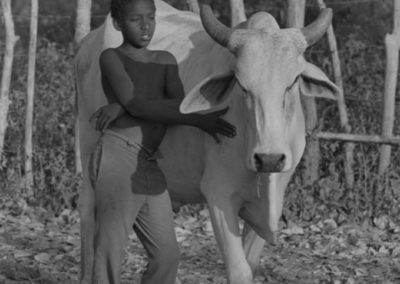

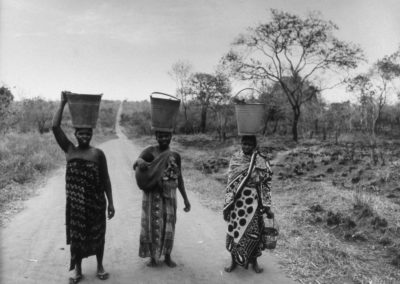

3) Inventory of male-female work roles. In the case of men: milking cattle, taking it to pasture, slaughter it, growing cassava, corn, bananas, building, hunting turtles, caring for horses. In the case of women: collecting water, taking care of children, cooking, washing clothes, grating coconut, maintaining the house, planting in the garden, buying supplies, selling goods in the Cartagena market.

4) Social organization. Rituals; ceremonies; special events such as marriages, deaths, births, baptisms, initiations, corralejas; recreational activities; the family structure; mother-daughter and father-son relationships. A day in the life of a family. The structure of the community, with leaders, authorities, decision-making powers, community meetings. The physical appearance of the Palenqueros, including clothing, jewelry, talismans, masks, hats, grooming, and haircuts.

5) Social change. Bus route to Cartagena, roads, transportation to the outside world, the influence of neighboring towns, electricity, plumbing, television, radio, newspapers, too little land for many people, migration abroad, the new land reform, exploitation by white people.

These categories, in addition to supporting the descriptive organization of the images, facilitated the development of research questions that appear in his notes kept in the archives of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center. For example, Cross wondered: “What are the factors that are accelerating social change in Palenque?” And in his notes, he recorded three factors and their visual imperative: “Road connecting Palenque to the highway (show use of this road by Palenqueros and by outsiders). Electricity/TV–radio (show Palenqueros watching TV and listening to the radio). Installment of plumbing (show women preserving the tradition of carrying water on their heads).”

The more than five thousand images provide a rich and detailed visual record of the life of Palenqueros and the material conditions of their subsistence and development. Four thousand of those images are already digitized with basic metadata and available to the public and researchers anywhere in the world. These images complement the 1,500 photos captured by Friedemann and that are in the Nina S. de Friedemann Fund of the Luís Ángel Arango Library.

The first edition of the book included only 260 black and white photographs, which were carefully selected to document and reveal the essence of the town and its people. These images tell us about their daily lives and their responses to the challenges of modernization and their adaptation and resistance to the demands of modern Colombian society.

Cross loaned his copy of the book to John Attinasi, at the time director of research at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at the City University of New York. Attanasi summed up the importance of translating and publishing the book in the United States in a letter addressed to the African-American writer Toni Morrison, then editor of Random House: “It would be a wonderful book to publish in English because it relates to African-Americans that are Hispanic and who have a unique language. Palenquero is the only Spanish-based Creole in the New World. The people also have many African-based customs and have not only resisted encroachment for several centuries, but a few who have ventured out have won world recognition in boxing, the sport which all (even women) practice.”[2]

Without a doubt, being part of this important study in Colombia served as an incentive for Cross to apply to the graduate program at the School of Anthropology at Temple University in Philadelphia in order to obtain a master’s degree in visual anthropology. In his application, Cross expressed that he wanted to improve his knowledge of anthropological methodology and theory and also gain film experience to make films and visual records that “could contribute to the science of anthropology and . . . to the understanding of who we are as human beings.”[3]

Upon completing his Peace Corps volunteering work on July 27, 1978, Cross decided to stay in Colombia as a freelance journalist and photographer and to finish Ma Ngombe. He developed the photographs used in the book in his studio in Bogotá. Undoubtedly, the work in Colombia turned to be very useful for his return to photojournalism in Central America, since it provided him with the methodological tools of visual anthropology to capture the last months of the Sandinista revolution.

————————–

[1] These manuscript notes by Richard Cross don’t have a specific date or title. They are archived at the Richard Cross Collection, Tom & Ethel Bradley Center.

[2] Letter from John Attanasi to Toni Morrison suggesting to her the publication of Ma Ngombe. May 29, 1980.

[3] Cross, Richard. Application to the Graduate School of Anthropology at Temple University. December 20, 1977.

The Nicaraguan Revolution

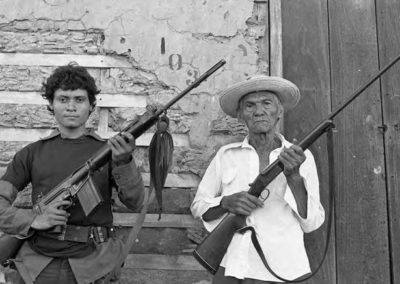

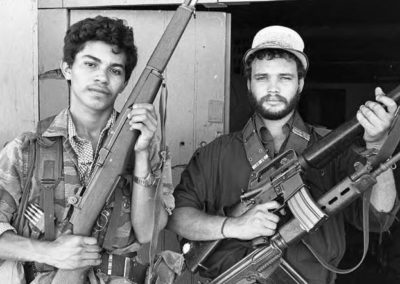

Richard Cross arrived in war-torn Nicaragua in early June 1979 and remained there through August 1979, writing and photographing as a stringer for the Associated Press. While there, he focused on documenting the last few weeks of Somoza’s rule in Nicaragua and spent much of his time in the city of León, the second-largest city in Nicaragua and, at the time, Somoza’s last stronghold outside Managua. In León, he photographed the impact of the bombings by Somoza’s forces on the population. He gained unfettered access to the Sandinistas and their actions and engagements. His photographs and stories appeared in different international publications, including Venezuela’s El Nacional, Costa Rica’s La República, Colombia’s El Tiempo, Cuba’s Gramma, and The Miami Herald. His work in Nicaragua earned him a nomination for the Pulitzer Prize by his editor at the Associated Press.

Also, Cross and the Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenal, at that time minister of culture, would publish the book Nicaragua. La guerra de liberación, a testament to the Sandinista struggle in Nicaragua. Published in 1982, the book (in Spanish and German) contains three poems by Cardenal and a foreword by Carlos Rincón, but the central part of the book is 76 black and white photographs by Cross. The selected images are devoid of any news scenes or public figures or rebel leaders. There is also no visual chronology of the war.

Undoubtedly influenced by the visual study of Palenque, where images cease to be representations of individuals to become visual referents of the collective, the Nicaraguan book focuses on the history and collective struggle. According to the detailed notes Richard Cross sent to Carlos Rincón for preparing the publication, the people who appear in the photographs “are not important because of their psychological (idiosyncratic) identity, but because of their social (group) identity.” The portraits of people “are not so much individuals, but archetypes of the Nicaraguan people.” His aesthetic vision was interested in showing opposing relationships, contrasts, in images—life and death, youth and old age, feminine and masculine, culture and nature, traditional and modern, heaven and the earth, and light and darkness. Thus, the book does not have captions or text to explain the images. Cross wanted to publish images that expressed his artistic, social and political vision of the Nicaraguan people’s liberation war.

It is no accident that the book ended with a sequence of six images of a Sandinista soldier in León painting a graffiti-poem on a wall with a two-page photo spread of the Sandinista soldier posing with a rifle and a can of paint in his hands. The graffiti is a poem by Rigoberto López Pérez about Anastasio Somoza Sr., whom the same poet shot in that city in 1956.[1]

Cross cared deeply about the Nicaraguan people he came to know and photographed and it is clear that he was deeply affected by their suffering when he noted in a letter that, “without realizing it, I have become committed to the people who are suffering down there. Covering the Nicaraguan revolution was the turning point, giving me a sense of direction and purpose.”[2]

————————–

[1] Letter from Richard Cross to Carlos Rincón, October 15, 1980. The graffiti poem reads: “The flowers of my days will be withered while the tyrant’s blood runs through his veins.”

[2] Menzies, op.cit., p. 70.

Visual Anthropology and the Parakuyo Maasai

Richard Cross returned to the United States in August 1979, shortly after the end of the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua. Though likely weary about his return to the United States since he had been abroad for several years, it was marked by his attendance to Temple University’s graduate program in visual anthropology. What began in San Basilio de Palenque with his work with Nina S. de Friedemann in 1975 continued in Philadelphia as he finally had the opportunity to begin his graduate studies.

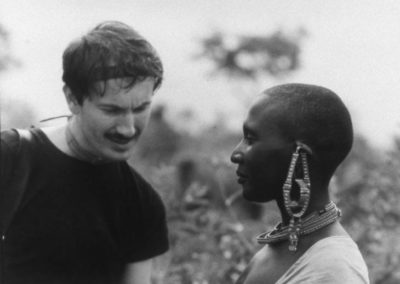

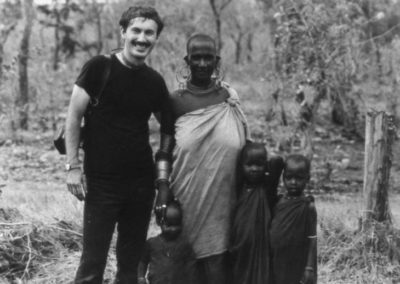

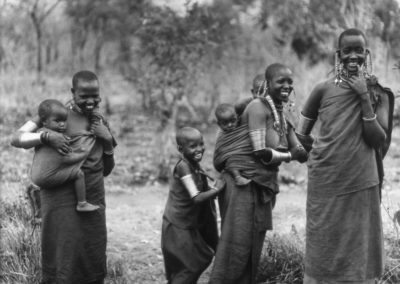

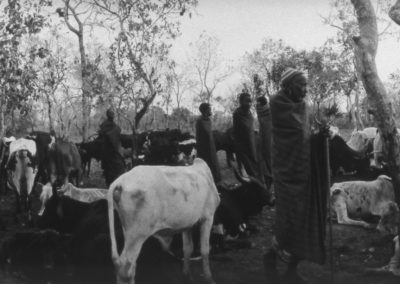

In the summer of 1980, one year after beginning his graduate studies, Richard Cross participated in an anthropological field project based on the Ilparakuyo Maasai, a pastoral people from Tanzania, Africa, proposed by him and doctoral candidate Peter Biella. Under the guidance of anthropologist Peter Rigby, Cross worked as a cameraman and photographer on an ethnographic film, titled Maasai Solutions, that focused on the Ilparakuyo Maasai’s interdependence with the Wakwere people and interpreted their system for dispute resolution within the context of the Maasai age-set system, drought, land shortages, and low population growth.

Over the course of his time in Tanzania, Richard Cross seamlessly entered the world of the Ilparakuyo Maasai. Professor Rigby cited that the way Cross got along with them was incredible considering that they could not communicate verbally and that there was a good relationship between them from the very beginning, calling it, “a oneness, a togetherness.” Rigby goes further in his appraisal of Cross’s treatment of the Ilparakuyo Maasai, noting that they trusted him and that he used the camera like a paintbrush, never taking anything away from anyone.[1]

While documenting aspects of Maasai Parakuyo culture, Cross and Biella also experimented with different techniques that made the camera replace and reveal the veiled staging of the motion picture camera. When Cross photographed, he preferred to use a Widelux panoramic camera, capable of taking photos up to 140 degrees, since its use highlighted the spatial component of the relationships between the Maasai Parakuyo and also their relationship with their environment. Cross argued that “a wider aspect ratio provides greater contextualization in the study of human behavior and interaction, and tends to define the individual more in terms of his social and natural environment; this in contrast to the traditional aspect ratio (in cinema, it is 1: 1.3) which emphasizes the individual over the group, and tends to alienate man from his environment.”[2]

However, whatever the method Cross and Biella used, it was clear that they had the trust and acceptance of the community, a fact that is evident in the 400 rolls of film (7,000 images) developed over the course of the month-long study in Tanzania.

As part of the graduate curriculum in anthropology at Temple University, Richard Cross moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico in the fall of 1980 to complete 2 semesters of graduate study at the Anthropology Film Center. Though Cross devoted himself to studying film, it was clear that, as Carroll Williams, then-director of the Anthropology Film Center, stated, photography was his strength.

By late 1980, Richard Cross felt ready to return to photojournalism in order to document the events unfolding in Central America. On February 13, 1981, he obtained credentials as a freelance photographer for the Associated Press.

————————–

[1] Menzies, op.cit., pp.85-88.

[2] Menzies, op. cit., pp. 89-93. Cross’s quote is from a letter he sent to photojournalism professor Karen Becker after hearing the presentation of her essay on the Weimar Republic workers’ photography movement. Archives of the Richard Cross Collection, Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, California State University, Northridge.

Cross in Central America

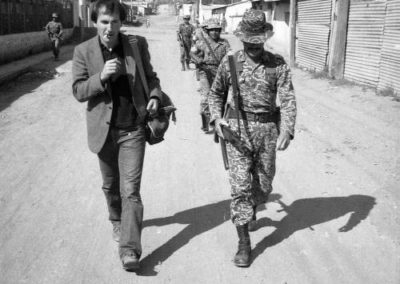

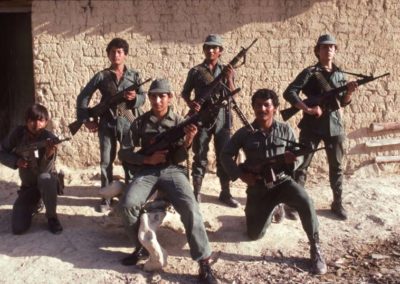

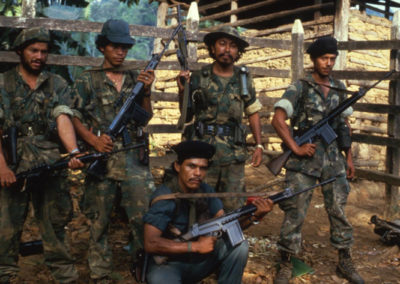

Throughout March and early April 1981, Cross’s most famous photograph appeared in Newsweek, Paris Match, and The Economist.[1] As narrated by Cross’s friend Nick Potter, the National Guardsman officer, whose name was José Neftalí Madariaga, was sitting out of uniform and asking Cross to take his photograph. When Cross agreed, the officer quickly put on his uniform and posed for the photograph, with a group of soldiers in the background who looked like statutes. He wanted a portrait and that’s how he wanted to be remembered.[2]

Unfortunately, Richard Cross had no time to bask in the international success of his photograph. Shortly after his return to Central America, his mother Françoise Cross was killed in March 1981 when a drunk driver collided with her car. Cross was very close to his mother and the tragedy of her death had profoundly affected him. In fact, he was so shaken by her passing that he put his career plans on hold, indefinitely, citing in a letter to Nina de Friedemann that, “life has been very difficult for me on many levels. . . with some help, I am better now but not really recovered enough to carry on without difficulty.”[3]

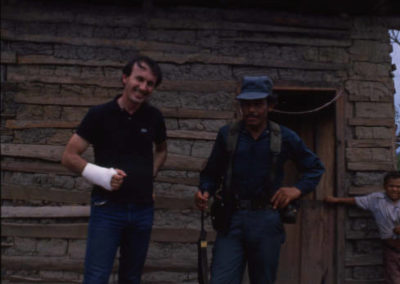

In March1982, Cross returned to Central America to cover the upcoming elections in Guatemala and El Salvador. In El Salvador, the political and social situation was quite complicated and dangerous. Murders were a part of daily life. The press did not enjoy any special privileges. Media stations had been shot with machine guns and bombarded with grenades. Several journalists had also died and/or disappeared, many by military forces. Four Dutch journalists had been killed by army forces.

Cross captured images for Newsweek of crowds at campaign rallies for José Napoleón Duarte and his Christian Democratic Party. Other images also began to be distributed by the Black Star agency. Cross also photographed Roberto D’Aubuisson at ARENA campaign rallies wearing an armored vest. He also took several photographs of members of the feared Atlacatl Battalion a few months after they massacred more than 1,000 people in El Mozote—one image shows a soldier holding a newspaper with the headline, “Vote Defeats Violence.” Some of his photographs in El Salvador were also included in the collective photographic book El Salvador, published the following year and edited by photographers Harry Mattison, Susan Meiselas, and Fae Rubenstein.[4]

At the end of the elections in El Salvador and Guatemala, Richard Cross returned to the United States in April 1982. During that time, he lived in Leawood, Kansas. From there, he was able to complete an assignment for a magazine devoted to soldiers of fortune and took about a thousand images of Harry Claflin’s survival school in Liberal, Missouri. Claflin was a veteran of the Vietnam War and was a mercenary and military adviser in Central America, training military forces in El Salvador and the Contras in Honduras.[5]

In late 1982, Richard Cross was ready to return to Central America. He rented an apartment in Mexico City and set about to photograph the thousands of Maya refugees living in Chiapas, Mexico, as a result of the Mayan genocide in Guatemala carried out by its military.

He visited eight refugee camps, documenting the lives of refugees and focusing mainly on camp geography and living conditions. Cross was so satisfied with his photographs of Maya refugees that he planned to use them as the foundation for his thesis at Temple University. Some of his photographs were even used in an exhibition and included in a book titled Guatemala: A Testimonial. His time in Mexico, however, was short.[6]

Richard Cross continued to travel to Central America as a freelancer. In March 1983, he traveled to document Pope John Paul II’s historic visit to Central America. In early April 1983, he returned to the United States, traveling to New York City to visit friends and contacts, and to secure permanent employment. His stay was short, however. By late April 1983, Cross returned to Central America, and this time, it was personal—he became engaged.

————————–

[1] Newsweek, March 16, 1981; Paris Match, March 27, 1981; The Economist, March 27-April 2, 1982.

[2] Menzies, op.cit., pp. 107-109. Cross registered de name of the officer in one of his slides.

[3] Ibid., p. 111.

[4] Cross’s photographs included in this important collective work (El Salvador: Work of Thirty Photographers) illuminate the destruction of infrastructure caused by the war. Few photographers systematically recorded the destruction of the environment like Cross. His work in Colombia is very important in this sense.

[5] Cavanaugh, Jack. “Soldiers of Fortune Meet to Share Arms, Tactics.” Los Angeles Times, October 27, 1985. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1985-10-27-mn-12693-story.html For a detailed account of the interconnection between U.S. covert operations in Central America and the contemporary white power movement, see Kathleen Belew’s book: Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America, pp. 77-100.

[6] Menzies, op. cit., pp. 131-137.

Killed in Action

With his return to Central America in April 1983, Richard Cross resumed his freelance work and he began a new partnership with U.S. News & World Report. Cross’s first assignment and the last of his life was to cover the activities of the U.S. advisors in Honduras and the activities of the Contras at the border with Nicaragua.

On June 21, 1983, only days after beginning his assignment for U.S. News & World Report, Richard Cross was killed in action. While on assignment covering the activities of the U.S.-backed counter-insurgency rebels (Contras) who roamed the Honduran countryside, Cross and his companion, Los Angeles Times Mexico City bureau chief, Dial Torgerson, were killed when their car exploded on a road along the Honduras-Nicaragua border.[1]

Almost immediately, the death of the American journalists sparked controversy as reports of the events were confusing. On June 22, 1983, the day after his death, the Ronald Reagan administration, by way of Secretary of State George P. Schultz, was quick to capitalize on the opportunity, blaming the Sandinistas in Nicaragua for the deliberate murder of Cross and Torgerson with a Soviet Union-supplied rocket propelled grenade. News outlets quickly parroted this information and the Nicaraguan government vehemently denied it, further confusing the situation.[2]

By late June 1983, news outlets reported that Richard Cross and Dial Torgerson were killed not by a rocket-propelled grenade as the U.S. and Honduran governments reported initially, but by an anti-tank mine. On June 29, 1983, the Los Angeles Times reported that Honduran military personnel investigated the site and found the damage consistent with that of a land mine because the white Toyota was lying on its side about 10 feet from a crater in the road about 3 feet wide and 2 feet deep. The left front tire of the car was about 100 yards from the wreckage. The Honduran military investigators found nearby the place where the journalists were killed two anti-tank M7-A2 and five M-14 anti-personnel mines, sold by the U.S. government to the Nicaraguan government when it was ruled by the Somoza dictatorship.[3]

Years later, Édgar Chamorro, spokesperson of the Contra during that time, expressed serious doubts about who was responsible for the killing of Torgerson and Cross. “There were suspicious circumstances surrounding the mining and several questions remain unanswered: Why, with commercial vehicles passing along the road regularly, did the mine explode only when the reporters’ car passed? Why didn’t the investigation specify whether the mine was a contact mine (which could be detonated by any vehicle) or a remote-control mine? As concerned as we in the leadership were for the safety of the reporters, we could not be in control of the activities of all the commanders in the camps, some of whom came up with crazy ideas. To this day I have my doubts about exactly how those reporters died.”[4]

————————–

[1] The Washington Post correspondent Christopher Dickey wrote a detailed account of the events before and after the deaths of Torgerson and Cross in his book on the Contras. The book also documents the violent excesses of some members of the Contra, including Commander Pedro Pablo Ortiz Centeno, aka El Suicida, whose group operated in that area. Cross photographed the group in Nicaragua for a few days. It is likely that this or another Contra group was responsible for laying the mine that killed the journalists. There was never an independent investigation of the events. With the Contras. A Reporter in the Wilds of Nicaragua, pp. 231-237.

[2] Reagan’s Office of Public Diplomacy for Latin America played a key role in creating confusion, attacking journalists, and selling the American intervention in Central America. Investigative AP reporter Robert Parry recounts how an officer of that office falsely accused his AP colleague Brian Berger of being a “Sandinista agent.” Fooling America: How Washington Insiders Twist the Truth and Manufacture the Conventional Wisdom, p. 211.

[3] Montalbano, William D. “Mine Killed 2 Newsmen, Honduras Says.” Los Angeles Times, June 29, 1983, pp. B8-9.

[4] Édgar Chamorro. Packaging the Contras: A Case of CIA Disinformation. pp. 32-33.

The Photographer’s Social Responsibility

In Central America, Cross, like several local and foreign photojournalists, tried to tell a story different from the official story that spoke of an East-West conflict, when the reality of the conflict was anchored in the North-South history of each Central American nation. Cross explained it in his notes about why he risked his life in El Salvador listing four reasons that combine the social, with the pragmatic, the personal, the professional, and the political.

“1) Social concern. This came as a result of living in a 3rd. world country for 5 years and experiencing first-hand the plight of the poor and class struggle.”

“2) Practical. Since photojournalism is a medium I’m committed to and trained for, and since I am not independently wealthy, I must make a living from this visual medium.”

“3) Sense of adventure maybe—escape the boredom and alienation one finds in U.S. society.”

“4) What does El Salvador have to do with the U.S.? Photographing war in Central America, for me, has to do not only with getting good shots which tell the news of the moment, but also with getting pictures which, when joined with other images and text, tell a story which reflects a more systematic and synthetic approach to the situation, an approach which is perhaps more historical because it attempts to show relationships existing between the present and the past. What is going on in El Salvador today is not unrelated to certain global phenomena—such as the decline of neocolonialism and the emergence of independent nation-states.”[1]

Cross’s photographs are a testament to a long-term endeavor that deviated from the norms imposed by traditional photojournalism. In an interview for the magazine News Photographer, Cross advocated for good in-depth photojournalism that instead of looking for the dramatic image that showed the symptoms of a problem, would focus instead on its causes in a systematic way, looking for patterns to explain it. “Which means,” he said, “that a person has to be dedicated enough to spend quite a long time with a story. And photographers have to take the initiative to try to have more control over the use of their photographs, and they have to get more interested in the potential for combining images to make stories and to combine images with text.”[2]

As the critic David Levi Strauss says, Cross explored this potential in several projects that culminated in either books (Colombia and Nicaragua) or an anthropological film (Tanzania). According to Cross’s academic advisor at Temple University: “His [Cross’s] interest from him in visual anthropology was motivated on two accounts. First, he expressed a keen curiosity for learning more about how photographs “worked” as a communicative medium—not simply as a technical process involving optics, grain structure, chemicals, or even in aesthetic terms—but more importantly, in cognitive, social, political, economic, and cultural contexts….Richard was not satisfied with merely getting the ‘right’ image—an image that conformed to an often unarticulated set of editorial decisions, sometimes aesthetic, sometimes political, as imposed by photo agencies and staffs of popular publications. It became clear that Richard felt a growing sense of responsibility for the images he ‘took from’ people and ‘gave to’ them to the viewing public. The political context of the image publications became an increasingly important problem in his practice of photography.”[3]

The publication of Ma Ngombe is in this sense paradigmatic of what Cross could not do in traditional journalism. In journalism, his images, as Strauss shows, were used as propaganda because they were taken out of context and placed in a hegemonic context in written articles in newspapers and magazines that reproduced the discourse of power. On the other hand, getting images of the Palenqueros at a certain historical moment was a long-term communicative process that counted, as it happened, with the approval and participation of the community, both in the production and in the circulation of those images, of his book, to the public of Palenque and, by extension, to the whole of Colombia. Today, the descendants of those Palenqueros from the 1970s (as well as those descendants of the Central American wars) can once again approach this complex social and visual reality, thanks in part to the work of this young North American photographer, who believed in a rigorous and systematic photography practice such as that of the social sciences, humanist as that of the best contemporary photojournalism and immersed for long periods in the community in order to better understand a group, a social collective. A photographic practice that looked at reality from within that social group, with it, and not outside of it.

————————–

[1] Cross, Richard. “Why Risk Life?” Manuscript notes with no date. Richard Cross Collection archive. California State University, Northridge.

[2] Strauss. “Photography and Propaganda: Richard Cross and John Hoagland in Central America and in the News,” p. 21.

[3] Strauss, op. cit., p. 21.

Bibliography

Attinasi, John. Letter to Toni Morrison at Random House recommending the translation and publication of Ma Ngombe. May 29, 1980. Richard Cross Collection archives, Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, California State University, Northridge.

Becker, Howard S. “Photography and Sociology.” Studies in Visual Communication 1(1), 1974, pp. 3-26. https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol1/iss1/3/

Belew, Kathleen. Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018.

Biella, Peter. Theory and Practice in Ethnographic Film: Implications of the Ilparakuyo Maasai Film Project. Ph.D. Dissertation. Ann Arbor: Temple University, 1984.

Cardenal, Ernesto and Richard Cross. Nicaragua: La guerra de liberación. Managua: Ministerio de Cultura de Nicaragua, 1982.

Cavanaugh, Jack. “Soldiers of Fortune Meet to Share Arms, Tactics.” Los Angeles Times, October 27, 1985. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1985-10-27-mn-12693-story.html

Chamorro, Édgar. Packaging the Contras: A Case of CIA Disinformation. New York: Institute for Media Analysis, 1987.

Cross, Richard. Gran application to National Endowment for the Arts, May 18, 1974. Richard Cross Collection archives, Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, California State University, Northridge.

——————-. Application to Temple University’s Graduate Department of Anthropology. December 20, 1977. Richard Cross Collection archives, Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, California State University, Northridge.

——————-. Letter to Carlos Rincón, October 15, 1980. Richard Cross Collection archives, Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, California State University, Northridge.

——————-. Letter to Karen Becker, no date. Richard Cross Collection archives, Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, California State University, Northridge.

——————-. “Why Risk Life?” Manuscript notes with no date. Richard Cross Collection archive. California State University, Northridge.

Dickey, Christopher. With the Contras: A Reporter in the Wilds of Nicaragua. Nueva York: Simon & Schuster, 1987.

Friedemann, Nina S. de and Richard Cross. Ma ngombe: Guerreros y ganaderos en Palenque. Bogotá: Carlos Valencia Editores, 1979.

Hughes, Jim. W. Eugene Smith: Shadow & Substance: The Life and Work of an American Photographer. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1989.

Lyon, Danny and Julian Bond. Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement. Santa Fe, Nuevo Mexico: Twin Palms Publishers, 2010.

Mattison, Harry, Susan Meiselas and Fae Rubenstein (photo editors). El Salvador: Work of Thirty Photographers. Written text by Carolyn Forche. New York: Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative, 1983.

Menzies, Lizabeth Jamieson. “Richard Cross: The Life and Death of a Photojournalist in War and Peace.” Master’s thesis. Syracuse: Syracuse University, 1985.

Montalbano, William D. “Mine Killed 2 Newsmen, Honduras Says.” Los Angeles Times, June 29, 1983, pp. B8-9.

Needle, June. “Kansas Peace Corps Volunteer Lends Communications Skills to Colombia”. Press Release by ACTION News, Peace Corps. December 1, 1976. Richard Cross Collection archives, Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, California State University, Northridge.

Parry, Robert. Fooling America. How Washington Insiders Twist the Truth and Manufacture the Conventional Wisdom. New York: William Morrow, 1992.

Strauss, David Levi. “Photography and Propaganda: Richard Cross and John Hoagland in Central America and in the News.” Strauss, David Levi. Between the Eyes: Essays on Photography and Politics. New York: Aperture, 2003. 12–41.

Tom & Ethel Bradley Center. Richard Cross Digital Collection. (11,722 images with metadata). California State University, Northridge, 2021. https://digital-library.csun.edu/bradley-center-photographs/richard-cross